para construirme

ni nivel se necesita

no más cierras el ojo

y ahí me voy hasta arriba

yo he servido por generaciones

a tus bisabuelos y abuelos

en mí han cocido

hasta las mejores tortillas

han calentado agua, han hecho jabón

y también me han usado para calentón

con la luz de mi lumbre

han estudiado infinidades de gente

tanta, que de mí

hasta se hizo presidente

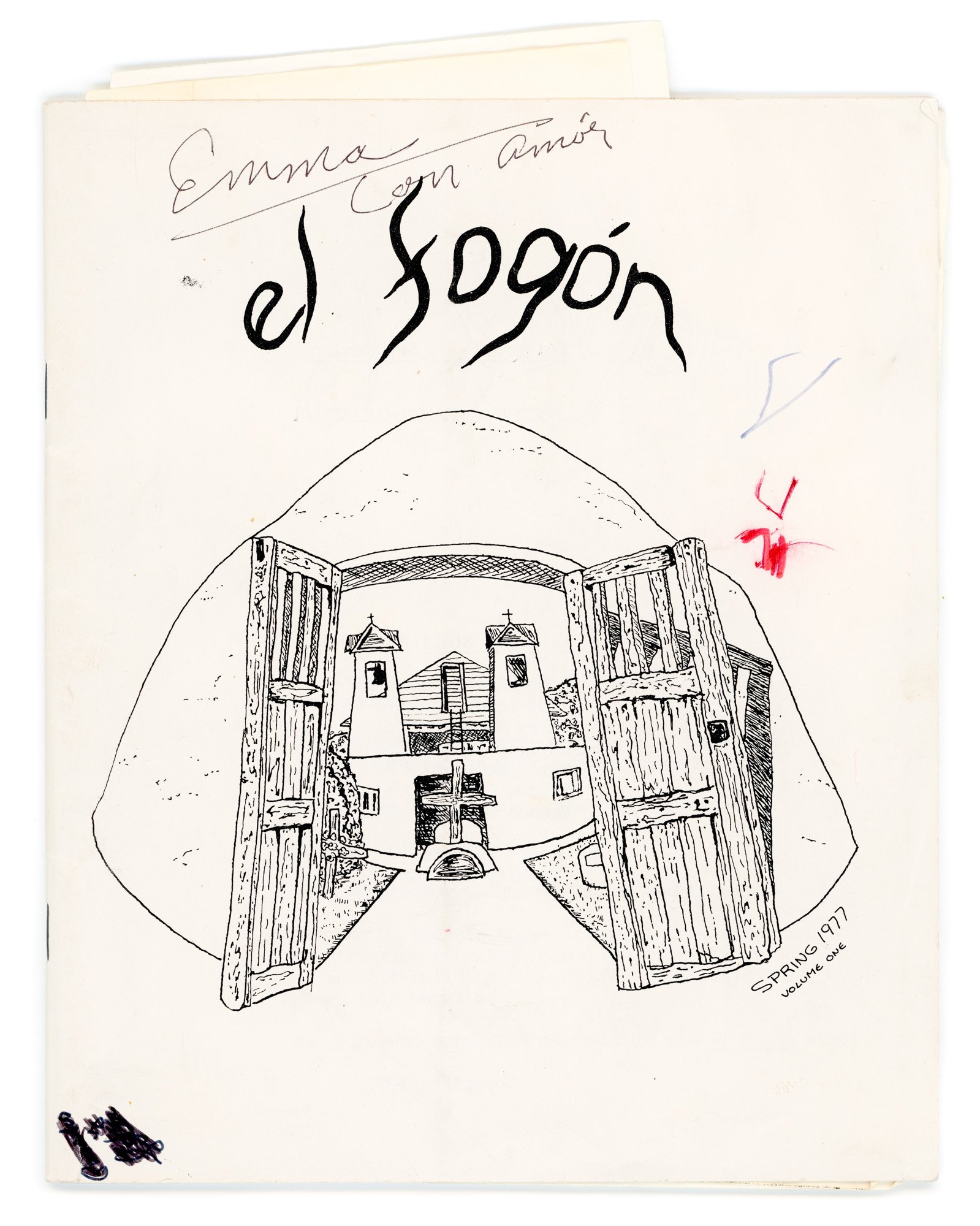

excerpt from

El Fogón de Adobe

by Alfonso G. Atencio, 1977